MENTORED BY A PICTURE BOOK

by Pat Miller

Writers often say theirs is a lonely job.

It’s true that when it comes to putting words on the screen or paper, it’s just you. But before that, accomplished authors will visit your home, stay for weeks, and show you exactly how it is done.

No need to feed them or put fresh sheets on the guest beds. You will invite them through their published works. Their books have successfully survived the journey you want to send yours on.

You can take theirs apart and figure out how they did it. Then you have a recipe for your own work. This process is called using mentor texts. The work of another is going to be your teacher.

Mentor texts have long been used in elementary classrooms to teach writing. Familiar books are used as exemplars of everything from using capitals in kindergarten to using humor in fifth grade.

Adult authors quickly caught on to how deconstructing a successful children’s book could be a private course in writing. Mentor texts can reveal how to build suspense, how to rhyme deftly, ways to pull on the readers’ heartstrings, and much more. Likely, this isn’t the first time you’ve heard the term. You may even have lists of mentor texts. But if you’re like me, you could use a demo on how to take one apart.

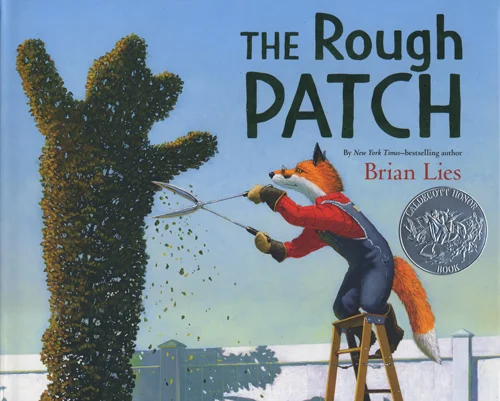

So, let’s do that now. I’d like to show you how I would take apart the 2019 Caldecott Honor book, The Rough Patch, written and illustrated by Brian Lies (Greenwillow Books, 2018).

The power of three + a keyboard

For picture book mentor texts, I read them three times. The first time is before I even know it will be a mentor. Not every book will meet your writing needs. This is another reason why writers read hundreds of children’s books. But you’ll know it’s a mentor when something about the story resonates.

The first reading is simply to enjoy the story. In The Rough Patch, Brian Lies tells the story of a fox whose beloved dog dies. It portrays his anger and grief in dealing with the loss of his best friend. It ends with hope.

The second reading is to savor the illustration. It’s a good lesson on how an illustrator can add to the richness of our text if we give them room. If you’re an illustrator, studying Brian’s book will show you how he brings the deceptively simple text to life.

Third, I read to dissect it (Spoiler alert: You might want to read the book before continuing.) Before the third reading, I type the book in a Word document exactly as it is on the page, double spacing between spreads. The beginning of The Rough Patch would look like this:

Evan and his dog did everything together.

They played games

and enjoyed sweet treats.

They shared music

and adventure.

Doing so allowed me to see the rhythm of the story, where the author wanted the reader to pause. In this short excerpt, I saw that Brian used just one adjective and no literary devices. Short and sweet. The illustrations show the characters’ personalities.

Analyzing the structure

The Rough Patch only has 365 words, but it delivers a powerful story. I wanted to see how Brian structured his story to do that.

The traditional three-act story structure has a beginning, a middle divided into two halves, and an end. Each act ends with a change.

The job of Act One is to introduce the characters and let us know the problem or what the main character wants. Brian creates an idyllic world in which the friends exist happily, and we settle in. What they want is unspoken—they want to keep enjoying one another’s companionship and their garden.

Then comes the inciting incident. It changes everything. On page 8-9, a double spread has just six words, But one day, the unthinkable happened. The dog is curled in his bed away from the reader. Fox kneels beside him with his paw on his friend’s shoulder. His ears and tail droop, his eyes are closed in sorrow, and the background on both pages is the empty white of shock.

Act Two, Part One, begins with the first plot point after the big change. Evan lays his dog to rest in the garden they both loved and nothing was the same. Those who’ve lost a loved one will understand the illustration’s background of various shades of scratchy blacks and browns. Evan grieves. Then comes the pinch point, the change that amps it up. Without forethought, Evan takes a hoe and slashes his garden to the ground. We see that grief can wreck you. Weeds take over the garden.

Act Two, Part Two, begins when a pumpkin vine crawls under the fence from his neighbor’s garden. He let it be.

Evan begrudgingly begins to care for the vine. A new normal begins as tentatively as a seedling. Evan eventually discovers a pumpkin beneath the vine’s leaves, and nurtures it for Fair Week.

The final act begins with another change that makes the resolution possible. Evan takes the pumpkin into town and ends up hanging out with other fox friends and enjoying the fair. It felt good to be out again, even if it wasn’t quite the same. Hope shines through for Fox and for the reader.

Evan’s pumpkin wins third place and Evan can choose between $10 or a puppy in a box. He chooses the cash but can’t resist taking just a little peek into the box.

The last page turn is hugely satisfying and filled with hope and promise for the future. The reader lingers on this illustration, bringing their own emotions to the ending.

Other teaching points

Story structure isn’t the only thing I can imitate from Brian Lies.

EMOTION: I also noticed how he pares down the story to its essentials without removing the emotion—a true gift. He does not use manipulation to make you feel sad. Nowhere in the story will you read sentences that tell about his feelings. Neither of these appear:

Evan was lonely without his dog. (telling)

Never again would he see his dog’s wide-faced grin or his liquid brown eyes. (manipulating the audience’s feelings)

I used a highlighter to go through the story and color the lines that elicited emotion from me. Like this one: If Evan’s garden couldn’t be a happy place, then it was going to be the saddest and most desolate spot he could make it.

Then I went through my own story looking for emotional resonance. Using a highlighter makes it evident that I needed more heart.

ADJECTIVES: Using another color, I highlighted all the adjectives in Brian’s story. There were few of them. Like this sparse but powerful sentence: Evan laid his dog to rest in a corner of the garden…” Brian didn’t get out the thesaurus and try to fancy up the nouns or verbs. He chose his simple words deliberately. I went back to my own MS and highlighted the adjectives. Was each one necessary?

ILLUSTRATOR NOTES: Granted, Brian doesn’t have to write art notes for his illustrator. Much of the richness of the story is in the illustrations. What can writers learn from this?

Note the simplicity of the text and the complexity of the illustrations. I discovered that Brian Lies’ sentences were crafted so artfully that they gave lots of possibilities and freedom to the illustrator, even if it hadn’t been himself. The beginning, shared above, contains just 19 words. Yet they gave the illustrator much to illustrate in a double spread and four art spots. Does my text do the same? Rarely does the writer need to give art direction, but the text has got to be alive with visual possibilities.

I always make a book dummy for my story. The Children’s Book Insider has a detailed article on how to do this at https://cbiclubhouse.com/clubhouse/how-to-make-a-picture-book-dummy.

Next, I find it helpful, using stick figures and rough sketches, to “illustrate” my story after I have laid it out in the dummy. If I find a page that I have trouble sketching, I know I need better words.

The next time you feel stuck as you write your picture book, or wonder how to improve your manuscript, head for the library. A habit of reading children’s books will provide you with lots of mentors to inspire, exemplify, and instruct.

Thanks to willing mentors like Brian Lies, writing no longer has to be a lonely business.

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Children's Book Insider, www.writeforkids.org. Reprinted with permission.

To learn more about Pat Miller and her work, go to